The new food economy – what’s driving consumer demand

Eric Jackson

Today, consumers want food they view as healthy, safe and nutritious, explains one Conservis founder, Eric Jackson.

“Anybody who's been tracking the new food economy for awhile sees headlines all the time about 'clean, free from,' right? There's kind of an 'I don't want this in my food' notion and then there's 'I want this in my food' and these labels just keep on popping up," says Eric. "This is not going to slow down anytime soon, so we what we see as a fractured food market means specialty opportunities for growers that want to participate, but it's complicated. There's not a marketplace on every corner and yet we want to help bring a visible marketplace for growers that want to participate in some of these specialty markets.”

What’s driving this? The smartphone. Right on the eve of when Conservis began, the smartphone came out which began democratizing the information exchange between people. You were no longer learning about your food only from TV advertisements, but you were telling each other stories via social media. Experts who track this data closely say that peer-to-peer is the most powerful information exchange and the smart mobile device platforms are what kicked this off.

What’s driving this? The smartphone. Right on the eve of when Conservis began, the smartphone came out which began democratizing the information exchange between people. You were no longer learning about your food only from TV advertisements, but you were telling each other stories via social media. Experts who track this data closely say that peer-to-peer is the most powerful information exchange and the smart mobile device platforms are what kicked this off.

Just over two thirds (78%) of consumers say a company's social media impacts their purchases. Millennials consist of those born between '82 and 2000. A whopping 83.1 million of the U.S. population fall into that category. Of those, 88% of them live in metropolitan areas, so you see the disconnect immediately between where they live and where their food comes from. “There are billions and billions of dollars wanting to participate in the new food economy," Eric said. "This is a big change because not long ago, the only deep pockets in agriculture were the big food and ag companies, and this wild card money came in from the outside and started changing the paradigm in the food and ag system.”

Just over two thirds (78%) of consumers say a company's social media impacts their purchases. Millennials consist of those born between '82 and 2000. A whopping 83.1 million of the U.S. population fall into that category. Of those, 88% of them live in metropolitan areas, so you see the disconnect immediately between where they live and where their food comes from. “There are billions and billions of dollars wanting to participate in the new food economy," Eric said. "This is a big change because not long ago, the only deep pockets in agriculture were the big food and ag companies, and this wild card money came in from the outside and started changing the paradigm in the food and ag system.”

Protection of the environment and supporting the farm community are popular themes for those buying organic. There's been an uptick in folks that are connecting with their food source and are now thinking about rural America. There was a study put out two years ago that shows that the counties that have a concentration of organic farming have a measurable uptick in the county gross domestic product (GDP), and that money usually stays local and cycles locally in the rural community.

“We're living in that era where big is bad, whether it's government, whether it's big food, whether it's big ag. Everybody's embracing small, everybody's embracing niche. Food and ag is so core to the way that people think about where they belong on earth.”

What does transitioning to organic look like on the farm?

Certification

Anders Gurda with the Farm Profit Program walks us through what to expect when you go organic. He also offers a suite of tools, resources, and referrals to help farmers see and seize the organic opportunity.

Anders Gurda

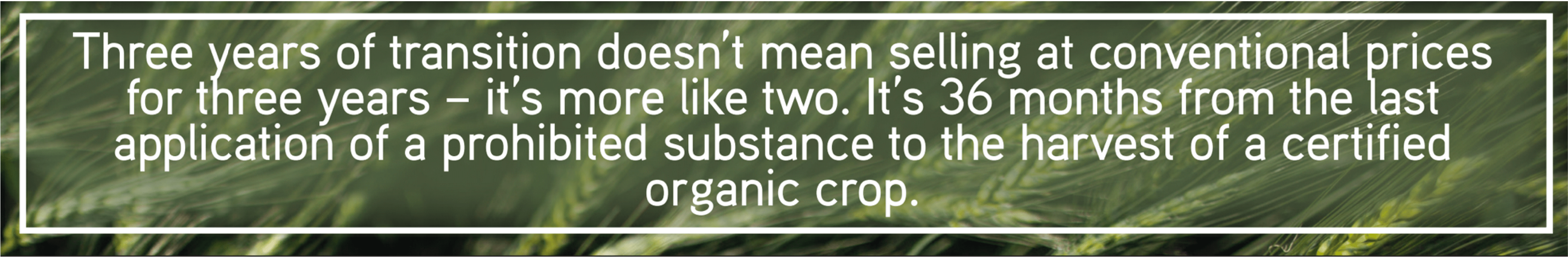

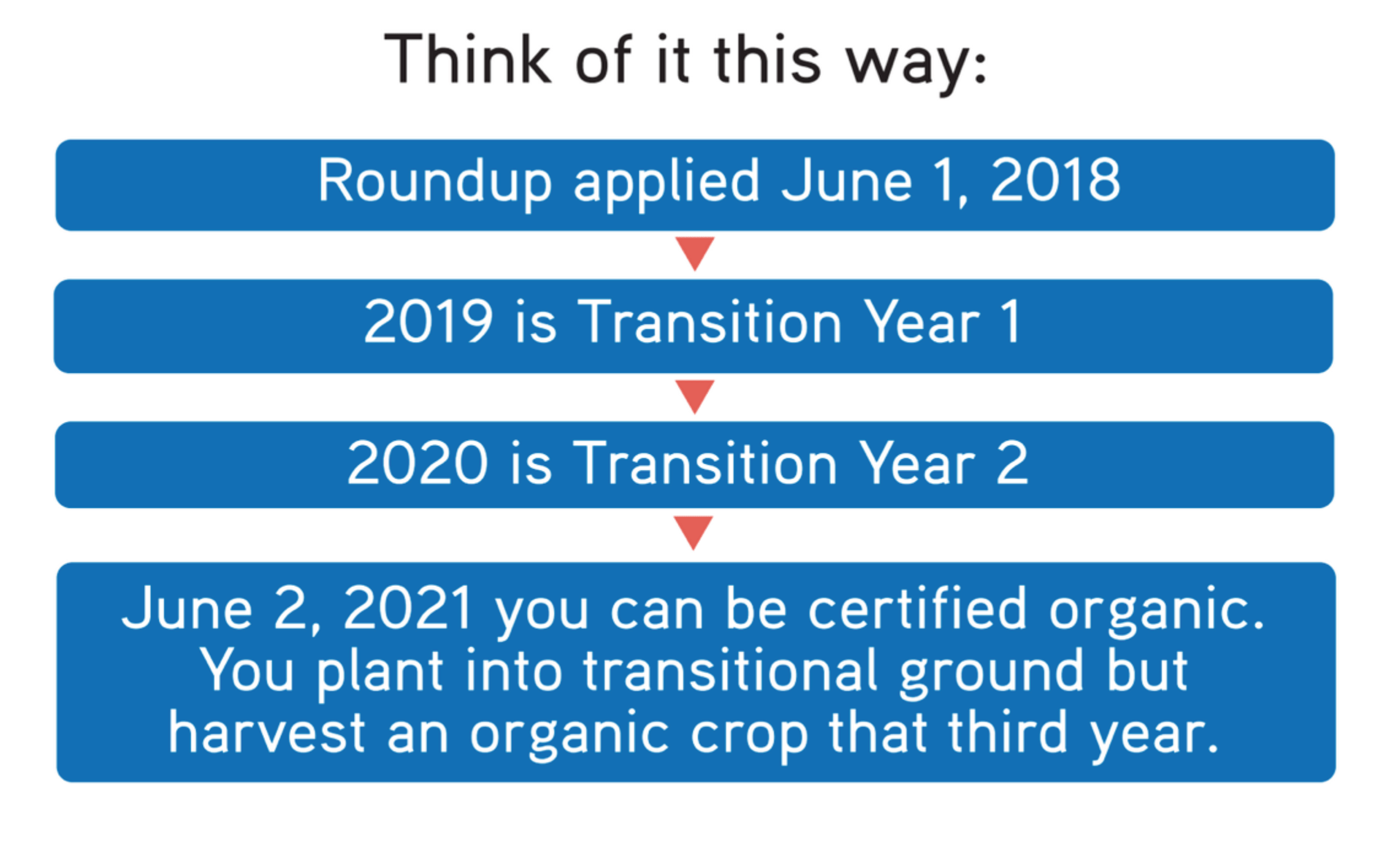

"The transition is an investment in two different ways," said Anders. "You're going to be investing in new tools like a weeder, instead of a sprayer. There's going to be a trade out of the tools of the trade that you use and you'll be investing in those. It's also an investment in the sense that there is an interval between the initial investment and recouping that investment which is three years, or 36 months for that organic transition."

Think of it as paying your tuition. You're navigating a pretty intense learning curve and you're paying your tuition through that 36 months. You're learning what you need to know to confidently and successfully get into the organic marketplace and become an organic farmer. It's also a marathon, again in two ways. The first is that you don't just go and run 26 miles without preparing, right? First you ran one mile and realize how out of shape you are, and then you run five and then you run 10 and you run 15, then you got to maybe to 20 once or twice and you're preparing to do this really damn hard thing, right? Organics is no different. Prepare for slow change where you adopt new practices in stages. Your operation isn’t likely going to withstand the shock of that new shift without slowly preparing for it. Three years can feel like a long time, but like a marathon, it can feel really good to finish.

Not everyone wants to run a marathon, pay that tuition, or make those investments and that fact is the very moat around your castle. Every record that you must keep, that's another shark in that moat. Those sharks keep your markets safe and other people from accessing that market. Organic in the agricultural space is one of the most protected in this way, and it's the reason that prices are $8 - $9 bushel corn right now. There's a reason those prices exist and it’s all the things in that moat that you're building a bridge over through that 36 months. For instance, the organic market is import dependent, not export dependent. Regarding trade wars and the geopolitical space, organic is relatively insulated from that. Growing organic is not just insulating yourself from competitors or others in the landscape, it's also somewhat financially insulated. That's your castle if you decide to make that jump.

Not everyone wants to run a marathon, pay that tuition, or make those investments and that fact is the very moat around your castle. Every record that you must keep, that's another shark in that moat. Those sharks keep your markets safe and other people from accessing that market. Organic in the agricultural space is one of the most protected in this way, and it's the reason that prices are $8 - $9 bushel corn right now. There's a reason those prices exist and it’s all the things in that moat that you're building a bridge over through that 36 months. For instance, the organic market is import dependent, not export dependent. Regarding trade wars and the geopolitical space, organic is relatively insulated from that. Growing organic is not just insulating yourself from competitors or others in the landscape, it's also somewhat financially insulated. That's your castle if you decide to make that jump.

The first misconception is that it will require three cropping years, and some people feel they cannot afford it. The reality is that it doesn't have to be three cropping years. It's really just two.

“That crop that you planted in 2021 was planted into what was transitional ground. It wasn't yet organic, but if you look at the top from the last application of a prohibited substance to the harvest of an organic crop (not the planting), you planted transitional ground. You are harvesting organic and likely that first year is going to be organic corn. That's your payout. It's actually two years, 2019, 2020, not three.

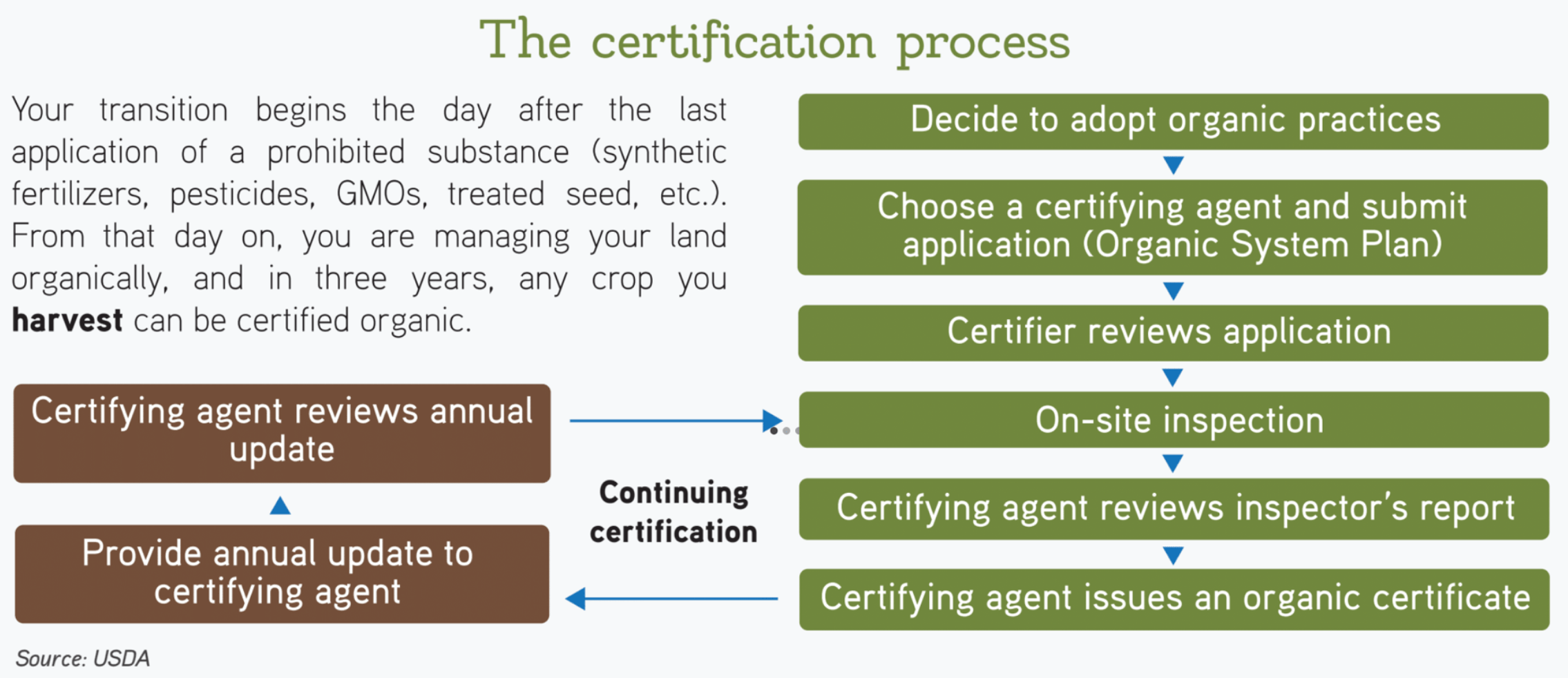

The certification process looks more complicated than it really is. Certification can appear to be the largest mountain to climb, but in truth it's not all uphill. There are currently 80+ certifiers in the country and they're all USDA accredited. The differences are going to be customer service, reliability, the kinds of language they use to fill out the forms, but otherwise they're very similar. You fill out an Organic Systems Plan (OSP), which is your roadmap. You'll indicate what you're doing, what your weed control strategy is, and what seeds you plan to plant. The certifier will help you through this and once approved, you move onto to the onsite inspection. If not, they'll help you iterate and figure it out until you can get there.

The inspector comes and they are not what you think of as a typical inspector- they're not out to get you! Oftentimes, the they are organic farmers and advocates themselves. “The organic inspectors are just there to inspect and report on what's happening," said Anders. "They're not making the decision so you shouldn't pay them off. You have to pay off the certifier afterwards. After that, the certifying agent reviews the inspector's report and if all looks good, you get your certificate. Simple as that and you do that every year."

Provide an annual update

“Every year, you provide an annual update," said Anders. "The agent will review onsite inspection if all looks good. If your OSP matches what you're doing on farm, then you get a certificate and that certificate is your ticket.”

Through your field history comes a verification of your organic eligibility. It's just saying that for three years from the last application that prohibited substance to my harvest, nothing was used that I can't use. No treated seed, no GMOs, no synthetic fertility, no chemical crop protection. If you do those things, you're good. If it's not your land, you must get an affidavit from the landowner or land manager saying that you're all good.

Regarding inputs, you need proof of purchase, volumes and application history for seeds, and any kind of biological crop protection. Anything that goes onto your farm for any reason, you need proof. Farm records are required; this is the who, what, and when. That's it! From planting and spraying, to cultivation in season and to harvest, track everything that happened. If you're already using Conservis' farm management system, a lot of that tracking is already done for you. It can be a picture on your phone that is time/GPS stamped. It can be a notebook in your pocket.

Required documentation for the inspector

Ensure that you track product from harvest to buyer, meaning it’s important to know the date and the yield, what bin it’s going into, and make sure that bin is labeled. Keep all the documents that accrue, including settlement sheets, bills of lading, invoices, receipts, and weight tickets. Keep these because when the inspector comes to your farm, they're doing mass balance and running the numbers to ensure they make sense, given the amount of seed you bought. They’re looking at your harvest and ensuring that what you sold feels accurate regarding yield to the end user. The purpose of this is simply to catch fraud, which has happened. Your ability to track your product’s movement is protection from fraudulent claims.

You must be able to document what you're doing to ensure your organic crops don't touch your (or your neighbor’s) conventional crops. You are allowed to have conventional and organic acres running parallel, but a grassy buffer strip between those fields should be documented.

The mental transition is likely the biggest transition on farm

The biggest transition to organic farming doesn’t necessarily occur in the field, but within the mind of the grower. Much of the mental transition comes down to optimizing long-term profitability. Consider spreading things out over time. One common strategy is to use alfalfa for those two years. Buy yourself some time, break your disease and pest cycles. Grow nitrogen at 170 pounds. Focus on good soil so that you can maximize first-year organic corn. And if you're getting $8-$9 for that corn, that's an investment that makes sense.

“Priorities, habits, motivations, those things are shifting. Refuse to believe that low yields and weedy fields are inevitable. They are not inevitable. With good management you can have yields that are on par with anything that you've ever done.”

Fertility and the organic system is really best thought of as kind of a flywheel. You're not just being able to feed with anhydrous, you can't use urea, you can't use these really soluble forms of nitrogen and other fertility, so it all depends on what is available and soluble within your soil. You get that flywheel turning slowly to begin with and then after two, three, four, five years, it's just whipping and that's what is actually feeding your crops into the future. This is true on any farm, but even more important in the organic system.

The learning curve

Optimizing your organic crops depends on observation though learning what's not working and then iterating, changing, evolving and adapting to that. “Doing the numbers is very important," said Anders. "Know what you're looking at as far as that transition, what your revenue is going to be, and make sure you can float it.” Start in the shallow end. Some growers jump in whole hog and are right in doing so, but they're ag engineers or they have the right type of mindset where they're able to do all their preparation in the years jumping up to that whole hog transition.

Optimizing your organic crops depends on observation though learning what's not working and then iterating, changing, evolving and adapting to that. “Doing the numbers is very important," said Anders. "Know what you're looking at as far as that transition, what your revenue is going to be, and make sure you can float it.” Start in the shallow end. Some growers jump in whole hog and are right in doing so, but they're ag engineers or they have the right type of mindset where they're able to do all their preparation in the years jumping up to that whole hog transition.

Lastly, think through where it makes sense to transition first. The farm land near your house is probably the best idea, as timing is really important. You're going to need to scout much more frequently. If you have a 24-hour window of dry weather to cultivate, you'll want to know exactly when that window is and you'll wish to readily get there. That could be the difference between a good crop and a crop loss.

Your better fields are oftentimes going to be the best ones to start with, so focus on fields that are well drained with low weed pressure. A lot of people leverage their Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) ground, which is not the best ground to begin with and they end up having failures. Some people are successful, but when you’re learning, give yourself the leg up and start with something that makes the most sense.

“Generally, I recommend transitioning 20% of your acres max, so that you're spreading your risk out and you're paying your tuition slowly.”

Interested is seeing how Conservis can help with recordkeeping and other organic requirements?